A Historical Novel by R. Reed Johnson

Preview 2

The black shroud of night enveloped me so that I could scarcely see. Yet, if I looked closely, I could make out the ghostly outline of my home at Shadycroft Farm. It was there that I’d just seen something that frightened me.

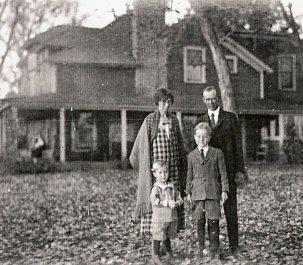

My grandparents, Herbert and Mona Johnson, had purchased Shadycroft Farm from Henry Harper Curtis in 1902. The original owner, Charles R. Bell, homesteaded the 365 acres of farmland in June 1877. After acquiring the land, my grandparents immediately set about building a large barn and enlarging the original farmhouse to accommodate their family of five children, later to be eight, of whom my father, Julius, was the oldest. Julius, in turn, purchased Shadycroft from his father in 1917, and ever since that time had been busily, and for the most part happily, engaged in farming. That is, he was, up until the time of my story.

There were four of us in our family — my dad, my mother (Grace), my brother (J. J.), and me. Actually, my brother’s name was Julius, same as Dad’s, and to begin with my folks called him Julius, or Julius Jr.. or, sometimes, just Junior — except Mother — she still called him Julius Jr.

There were four of us in our family — my dad, my mother (Grace), my brother (J. J.), and me. Actually, my brother’s name was Julius, same as Dad’s, and to begin with my folks called him Julius, or Julius Jr.. or, sometimes, just Junior — except Mother — she still called him Julius Jr.

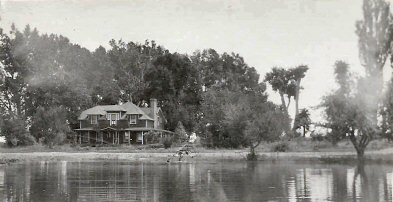

Our farmhouse at Shadycroft was a large, comfortable home with a gabled roof and wide, shady porches. It was set in the midst of numerous large cottonwood and elm trees, and ordinarily I would have derived a good deal of comfort from its reassuring presence, but tonight was different. Accompanied by Rab, a big, black

German shepherd, I was returning from an afternoon and evening of play with Charley Vogel, the boy who lived in the house at the head of the lane.

German shepherd, I was returning from an afternoon and evening of play with Charley Vogel, the boy who lived in the house at the head of the lane.

At that time of my life, next to Rab, Charley was my very best friend. There were several reasons for this. First of all, he'd just turned ten years old and I was a little over nine months older, making me, in my considered opinion, much his superior in most every respect. Second, he had an older sister, Abigail, and just recently I had begun to realize that there were some very interesting differences between boys and girls. Third, his mother, who was a widow lady, made really great chocolate cookies; and fourth, and maybe most important, there was no other playmate to be had for miles around.

I should have gone home long ago on strict orders from my parents. On this particular Friday night, they and J. J. were in town attending a meeting at the Grandview Grange. Ordinarily I would have gone with them, but that afternoon they had agreed to let me stay and play at the Vogel’s, just as long as I promised to be home well before dark.

Perhaps I should point out that this concession on the part of my parents had come only after an unusually eloquent appeal on my own behalf in which I pointed out that, being as how I was almost eleven years old, I was perfectly capable of taking care of myself — especially without the help of my fifteen-year-old brother. To my considerable surprise, they had agreed, but only after I had assured them that I would be home well before dark and that I would comply with my mother’s long list of “do and don't do” instructions regarding my behavior.

Later that afternoon, just as the sun was disappearing behind Mount Evans, Mrs. Vogel suggested that perhaps I should give serious thought to leaving because it would soon be getting dark. But, inasmuch as I appeared to be well on my way to winning all the wooden kitchen matches in a spirited poker game with Charley and Abigail, I could see no compelling reason to hurry my departure. So I chose to ignore Mrs. Vogel's comment regarding the rapidly approaching night. I ignored, too, her gently added reminders that my mother's wrath, when aroused, was a significant force to be reckoned with, and, besides that, it was getting dark and she was sure that it was going to snow.

After another forty-five minutes of play and after losing most of my hard-won matches — to a girl, of all people — Mrs. Vogel’s admonitions finally arrived at the reasoning part of my brain — particularly the part about my mother's wrath. Belatedly, I decided that it really was time to go home — well past it, as a matter of fact. So here I was, shrouded by the blackest of nights, wishing fervently that I had not been so successful in convincing my parents that I could take care of myself without their help — or maybe even my brother’s.

I was standing at the end of Windermere, the narrow, rutted road leading to Shadycroft Farm from the small town of Littleton about three miles to the north. I was staring intently down the lane at the shadow of my home a quarter of a mile away. I thought I had seen a faint glimmer of light coming from the east end of the house, right where the kitchen window was situated. It was there for only an instant and then gone. Had I really seen anything? Surely it was my imagination. Halloween was just a few days past, and I succeeded in convincing myself that it was only my recent involvement with ghosts and witches and my rampant imagination that led to my disquietude. That my imagination was rampant had been pointed out to me on innumerable occasions by my parents as well as by my brother, all of whom were frequently not pleased, and often downright critical, of the end products of my active, and what I considered rather creative, mind.

Grateful for Rab's reassuring presence by my side, I resumed my walk down the lane but with noticeably less enthusiasm. The wind was cold and sharp and out of

the north. It whispered ominously through the dried and shriveled leaves of the cottonwood trees that overhung the lane, composing a sinister symphony that contributed mightily to my increasing feeling of unease. I thought briefly of returning to the haven of the Vogel’s warm and safe kitchen, but I immediately gave up the idea on the mistaken belief that whatever might await me down that dark and forbidding lane couldn't possibly be worse than the humiliation and teasing I would be forced to endure should I timidly return to the shelter of my friend's home. How wrong I was!

the north. It whispered ominously through the dried and shriveled leaves of the cottonwood trees that overhung the lane, composing a sinister symphony that contributed mightily to my increasing feeling of unease. I thought briefly of returning to the haven of the Vogel’s warm and safe kitchen, but I immediately gave up the idea on the mistaken belief that whatever might await me down that dark and forbidding lane couldn't possibly be worse than the humiliation and teasing I would be forced to endure should I timidly return to the shelter of my friend's home. How wrong I was!

Two thirds of the way down the lane, I stopped again — abruptly — and so did my heart. I felt certain that I had again seen a faint yellow glow flicker very briefly, this time from the small dormer window in the attic directly above the kitchen where earlier I had seen, or at least thought I had seen, the first glimmer of light. Except for storage, the attic was seldom used. It was accessed from below by a stairway from the laundry room that adjoined the kitchen, as well as by a door from the upstairs hall. Surely it was a gleam of reflected light, I told myself, although from what source I couldn't possibly imagine, black as the house and the world around it now were. My heart had commenced beating again, and for that I was most grateful. But where were my parents? They should have been home long before now — and besides that, how come they let a ten-year-old kid talk them into going to the Grange meeting, leaving him home alone to fend for himself against all manner of scary things? — I wished now that I hadn’t been so persuasive.

The temperature was dropping rapidly, the ever-increasing wind driving sharp needles of snow, stinging my face and forcing the bitter cold through the layers of my clothing. It was not a time to dally. I had to decide, and decide very soon, whether I should go on to my home, which now was very near by, or seek some other shelter from the storm. My options were few. I had already dismissed going back to the Vogel’s house for reasons that I foolishly still thought valid. I considered trying to get to the Williamson‘s house, perhaps a third of a mile farther west in the lee of the bank of the Highline Canal, where it wound its way through our property. Clyde Williamson worked for my dad and lived in the tenant house on our farm with his wife, Ada, and their two daughters, Blanche and Frances. I had seen them leaving in their old Star touring car during the late afternoon, and I was pretty sure that they hadn't come back yet. I could see no light in the direction of their house, but by now the blowing snow limited visibility to no more than a few feet.

I thought briefly of taking shelter in the barn on the other side of the canal or in one of the chicken houses. I had spent many hours working and playing in our barn. It could be scary enough in the day time, but at night, in a storm, with the wind howling through the rafters like a banshee, I was certain that it was no place for me.

The chicken houses were even less inviting. Somehow the thought of snuggling up to thirty or forty whiterock hens and roosters wasn't particularly appealing — due, in part, to the intimate knowledge of our chicken's unsanitary habits I had acquired through seemingly endless hours spent cleaning up their messes. Let me tell you — chickens are not neat. Even in the brief time spent considering these options, the temperature had dropped several degrees and the wind seemed to double in intensity. I had no other choice — I had to go into the house.

Actually, all seemed peaceful and serene in the big house now. Certainly there was no sign of a light anywhere that I could see, and I became more and more convinced that I had only imagined that I had seen anything worrisome. Retrieving the door key from where it was hidden on the ledge over a nearby window and keeping Rab close beside me, I stepped cautiously onto the porch and walked to the front door. After taking a deep breath, I reached out to insert the key into the lock, but at the slightest touch, the door slowly swung open to reveal the pitch-black interior of the entry hall. The door was already unlocked! It wasn’t even closed tightly.

Anxiety flooded over me. I couldn't stop shaking, whether from fear or from the cold, I couldn't be sure. I forced myself to breathe. No sound was to be heard, other than the wailing of the wind through the cottonwoods. Nothing moved — including me. I stood riveted to the door threshold. After what seemed an eternity, I whispered softly to Rab and was relieved to feel the reassuring pressure of his big head nudging my leg. As far as I could tell, he wasn’t a bit concerned. Taking a deep breath, I groped inside the doorjamb searching for the light switch. The click of the switch sounded like a rifle shot, but how I welcomed the flood of light that filled the entry hall, revealing nothing more sinister than our hall tree festooned with a variety of familiar hats and coats.

Turning on every available light as I went, I entered the living room and flopped down on the sofa — Rab flopped down beside me. I had to think — why didn’t my parents lock the door when they left like they usually did? Probably, I thought guiltily, it was because they were counting on me to lock up when I came home before dark as I had promised.

Up until then, there never had been much crime in Littleton and the farms around it. Except for a robbery at the Littleton National Bank back in 1928, it had always been quiet and peaceful. According to the write-up in the Littleton Independent, George Malcolm was working in the bank that day and according to him, the bankrobber stole over eleven thousand dollars — neither the robber nor the money were ever seen again. But just in the last year or two lots of hobos had been coming to Colorado from Kansas and Oklahoma after they were forced to leave their farms and home by the drought and blowing dust. Most of them just wandered from house to house, asking for food and money and didn’t cause any trouble. But every so often, I’m sorry to say, one of them would rob somebody or somebody’s home. And according to my folks, there was another reason that so many homeless people were showing up around Littleton back then. It was on account of what they called the depression — and it wasn’t just in Colorado People all over the country were out of work and hungry – farmers and towns people alike. Partly it was because of the drought and partly it was due what my folks called the failed economy.

But it was the bootleggers that worried me the most. According to my friend Joe Wilkinson, a gang of them was making moonshine whiskey in a house up on Windermere, less than two miles north of our farm. I don’t know how he knew that, but he swore it was gospel truth. So I guess it wasn’t too surprising that my folks had started locking the house whenever they were going to be away — except for today, of course, when they were counting on me to lock up when I got home.

But how come the door wasn’t even shut completely? Could somebody have come in the house after we all left? But why didn’t they close the door? Were they afraid it’d make some noise and someone inside the house would hear it? Could they still be in the house?

And where were mother and dad and J. J.? They should be home by now. At least they could have called me on the telephone to tell me they were going to be late. Of course, maybe they did and I wasn’t here to answer. But I probably was worrying needlessly. Except for the storm outside, everything was quiet and peaceful in the house, and all I had to do was just sit tight and wait for my folks to get home. Actually, there was something I could do. I could ask the telephone operator to call the Grange hall so I could talk to my folks if they were still there — just hearing their voices would make me feel better. It was Friday night and Myrtle should be the operator on call. I liked Myrtle. She was nice, and right then the thought of hearing any familiar voice was mighty appealing. The telephone was on the desk in the entry hall. I quietly lifted the receiver from the hook in order not to avoid alerting anyone or anything that might be lurking on the other side of the door that opened into the east part of the house. I waited for the operator to answer and ask me what number I wanted. Nothing! Not a sound could be heard. Apprehensively, I jiggled the receiver hook up and down several times, but all I could hear was the sound of my heart beating faster and faster as I held the receiver tight to my ear. There was nothing, no sound at all — only silence. The line was dead.

I knew very well what had happened. A tree branch, burdened by the weight of the snow, must have broken and fallen across the telephone wire snapping it in two, leaving me cut off from the outside world and, except for Rab, completely alone — or so I sincerely hoped. It had happened many times before, and I knew the line wouldn't be repaired until tomorrow at the very earliest. Accompanied by Rab, I slowly returned to the sofa and sat down. He laid his big head in my lap and wagged his tail reassuringly, as though to tell me that he would keep me from harm. I hugged him around the neck, grateful for his presence.

Well over an hour crept by and still no sign of my parents — I was getting more and more anxious by the minute. I felt sure that they had tried to get home and had gotten stuck in a snowdrift somewhere between here and the Grange hall. Windermere was deeply rutted even in the best of weather, and now, with the ruts buried by a heavy blanket of snow, it would be difficult to keep the car from slipping off the road. But even if that had happened, I was sure they’d take shelter at one of the farmhouses along the way. So I really wasn’t worried about my parents or J .J. — partly because I knew they were safe — but mainly because I had enough problems of my own to worry about.

The storm was steadily increasing in fury. At times, when the wind subsided, I would hear the sound of breaking tree limbs and the harsh rasp of wind-driven snow against the windowpanes. At irregular intervals, a disturbing thumping noise came from the direction of the kitchen, creating mental images of something huge and fearful attempting to force its way into the house. "It's only the wind banging a branch of that old box elder tree against the side of the screened porch," I told myself unconvincingly.

Abruptly, my anxiety was increased a hundredfold by a momentary flicker of the overhead lights. I’d forgotten. If the telephone line could break, so could the power lines, and at any moment I might find myself in total darkness. It happened every time we had a bad snowstorm. As far as I knew, all our flashlights, kerosene lamps, and candles were in the kitchen and dining room. Both were places I definitely did not want to go. Hoping that there was one at this end of the house, I decided to make a search — maybe I’d get lucky and find one — although the thought of doing it while there might be an intruder skulking in the house was worrisome to say the least. (I had recently learned the word “skulking” while reading one of my favorite Zane Grey books.)

Mustering what little courage I had left and keeping Rab close by my side, I carefully explored the newer part of the house, both downstairs and up, through more rooms than I seemed to recall the old house having. Happily, my search was successful, for I found a flashlight in a bureau drawer in my parent's bedroom at the southwest corner of the upstairs hall. It was a welcome sight.

My most exciting discovery, however, was a .44 caliber Colt revolver, sheathed in a well-worn leather holster and cartridge belt hanging from a hook on the back of the closet door. I recognized it. It was the gun my Granddad Johnson had used back in the 1880s, when he carried the mail on horseback from a small town on the eastern plains of Colorado called Longmont to a little community in the mountains called Estes Park. I remember him telling me once how grateful he was that he’d never had to use it to shoot a bad man — I found that very disappointing.

I remember my dad calling it a "hogleg" because of the shape of the grip. He also mentioned that the one and only time he'd ever shot it, the recoil had taken most of the skin off the palm of his hand. I could just imagine what my mother's reaction would be should she realize that I had found this treasure and what I thought I might do with it — I'd be in big, big trouble. My dad would be in even bigger trouble, however, for having left it where I could find it. The rest of his guns, including my own .22 caliber Winchester and 410 shotgun, were securely locked in a cabinet in the entry hall closet. They'd all been put there on strict orders from my mother right after Dad shot a hole in the kitchen door while cleaning a twelve gauge shotgun he thought was unloaded. The fact that no one had been hit was a minor miracle: that Mother had agreed to his keeping his guns at all was a major one.

I remember my dad calling it a "hogleg" because of the shape of the grip. He also mentioned that the one and only time he'd ever shot it, the recoil had taken most of the skin off the palm of his hand. I could just imagine what my mother's reaction would be should she realize that I had found this treasure and what I thought I might do with it — I'd be in big, big trouble. My dad would be in even bigger trouble, however, for having left it where I could find it. The rest of his guns, including my own .22 caliber Winchester and 410 shotgun, were securely locked in a cabinet in the entry hall closet. They'd all been put there on strict orders from my mother right after Dad shot a hole in the kitchen door while cleaning a twelve gauge shotgun he thought was unloaded. The fact that no one had been hit was a minor miracle: that Mother had agreed to his keeping his guns at all was a major one.

I was sure it was on account of the recent robberies in Littleton that Dad had hung the revolver in their bedroom, figuring it would be a handy and safe place to keep it in case he ever needed it. Obviously, he had forgotten my tendency to investigate — snoop was the word my brother would have used. Anyway, I was sure that Dad would hear from my mother in no uncertain terms when she discovered that I had found it, but right now it seemed like a gift from heaven.

Dragging it down from the hook, I strapped it about my waist. Fortunately, Dad was a small man, and the extra holes he had poked through the belt to make it fit his waist just barely sufficed to keep it hanging precariously from my own scrawny hips. I pulled the revolver from the holster with some difficulty. It was real heavy, and I doubted that I could actually shoot someone, even if the need arose. I'd be far more likely to shoot off my foot or some other valuable body part. At that moment, however, such a possibility didn't particularly concern me as I loaded the gun with bullets from the cartridge belt, put it back into the holster, and, cowboy fashion, swaggered back into the hall and down the stairs, certain that I was the spittin’ image of Buck Duane.

Buck was my current cowboy hero, having recently seen Zane Grey's The Last of the Duanes at the Gothic Theater in Englewood, a small town several miles to the

north of us between Littleton and Denver. Actually, Buck and I might easily have been mistaken for brothers, except that Buck didn't seem to have the annoying problem of having his gun belt fall down around his ankles as he walked. Fortunately, I hadn't come across any unwanted visitor during my search, although the thought had been foremost in my mind. Unhappily, I had found only one flashlight. All of the others, along with the lamps and candles, were in the dining room or kitchen – places I definitely did not want to go.

north of us between Littleton and Denver. Actually, Buck and I might easily have been mistaken for brothers, except that Buck didn't seem to have the annoying problem of having his gun belt fall down around his ankles as he walked. Fortunately, I hadn't come across any unwanted visitor during my search, although the thought had been foremost in my mind. Unhappily, I had found only one flashlight. All of the others, along with the lamps and candles, were in the dining room or kitchen – places I definitely did not want to go.

As I returned to the living room sofa, my stomach growled loudly, reminding me that I hadn’t eaten since lunch and was hungry. On top of that, the temperature inside the house was dropping rapidly ,making it obvious that the furnace in the cellar needed stoking. Well, I'll tell you right now, there was no way I was going down into that dark, dank dungeon and add coal to the furnace. Compared to that gloomy, black widow-infested region, a visit to the kitchen was like a pleasure trip. In the kitchen, a big wood-burning range would make short work of the cold, and in the dining room, the "Round Oak" stove with isinglass windows in the door would do likewise. And, best of all, there was plenty of wood in the wood box, coal in the coal bucket, and food in the pantry. It was becoming more and more apparent that, despite what I hoped were my silly imaginative fears, I had to venture into the kitchen to avoid starvation and to keep from freezing to death.

The storm was abating. I no longer could hear the tree branches banging on the side of the house. In fact, there was no noise at all — silence enveloped the entire house. I should have been grateful, but, while the racket from the storm had been frightening, the complete quiet seemed far more unnerving. I whispered to Rab. He responded by thumping his tail on the rug, grateful that I had acknowledged his presence but not nearly as grateful as I was for his company.

With resolve, I rose from the sofa. It was time to put an end to my foolish fears as well as to my hunger and cold and go to the kitchen. With Rab close by my side, I walked towards the entry hall, but the moment I entered, the light in the hall flickered once and then went out, leaving a terrifying darkness in its stead. I couldn't believe it. Now the power line was down — what else could go wrong? I wondered if perhaps this was an omen that the dining room and kitchen were not safe places to go. But what else I could do — other than sit in the living room in total darkness, shaking with cold, and fear, and hunger.

Taking the flashlight from my jacket pocket, I pressed the switch and watched in horror as a sickly, yellow shaft of light extended from it for no more than a foot or two before it vanished in the black interior of the entry hall. The battery was weak, almost gone! After turning off the flashlight in order to conserve what little power was left, I stood shaking with fright in the suffocating darkness.

Up to this point, I had succeeded fairly well in overcoming my earlier anxiety, but now the prospect of having to search for the lamp and matches in total darkness raised new and fearful specters in my mind. What if some fearsome creature should leap upon me in the dark! The thought terrified me. But I still had no other choice: I had to find the kerosene lamp and light it before the power in the flashlight died completely. To avoid using the flashlight until I really needed it, I groped in the dark — first for Rab's reassuring presence, and then for the door leading into the dining room. I was surprised when I took hold of the doorknob. For some reason it felt wet and sticky, almost slimy. But I thought little of it at the time as I peered into the black interior of the dining room. The lamp should be on the table in the center of the room, but I wasn't so sure about the matches. Stepping cautiously in the dark, I bumped into the edge of the table sooner than I had expected, creating an unnerving squeak as its wooden joints rubbed together.

Reaching out carefully in the dark, I moved my hand back and forth across the tabletop until I found the lamp, but, search as I might, I could find no matches. I had to use the flashlight. Praying fervently, I pressed the switch and sighed in relief as a weak ray of light dimly illuminated the surface of the table. My hand was still sticky from touching the doorknob, and, without thinking, I directed the weak beam from the flashlight towards it. I stared in horror — my hand was covered with blood!!

A Thread of Gold

is available now. Ordering

information can be found here!

Home

Preface

Preview 1

Preview 2

Preview 3

About the

Author

Shadycroft

Farm How

To Order Resources

Copyright © 2004 R. Johnson. All Rights Reserved.